HYMENOPTERA Bees, Wasps, Sawflies & Ants etc

SUB CLASS Endopterygota

COMMON FEATURES

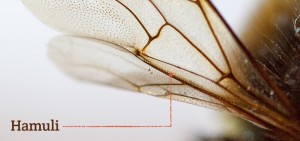

Minute hooks on the hindwings, called hamuli, that can attach to, and disengage from, the forewings.

EASE OF IDENTIFICATION FROM PHOTOS

Relatively easy to impossible!

KEY IDENTIFICATION FEATURES

Wing venation, especially the sub-marginal cells.

Wing venation, especially the sub-marginal cells.- The way the thorax joins the abdomen separates sawflies from the rest of the hymenoptera (see Brief Introduction, below).

- The ovipositor, an extreme modification of the final abdominal segment, which can be used for egg-laying or stinging in females.

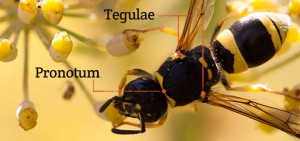

- Parts of the thorax, notably the pronotum (a plate or collar-like structure at the front of the thorax) and tegulae (little knobs at the base of the wings).

- Abdominal markings can help identification especially with bumblebees and social wasps.

IDENTIFICATION OVERVIEW

Hymenoptera are arguably the most mind-bendingly difficult order to identify either from photographs or specimens. Some are reasonably straightforward, such as bumblebees and social wasps, but as soon as you enter the murky world of sawflies, solitary bees, solitary wasps and ichneumons, well that’s a different matter. They come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, are often grouped by developmental criteria, can look similar even if they’re not in the same family and once you do manage to get down to family level – or further – some species are virtually identical. Add in the fact that most sources of reference for these insects can be highly technical, difficult to obtain, scattered all over the place and bloody expensive just compounds the problem. And lastly, much of the reference material I have says you can’t identify many of the species from photos anyway! Personally, I don’t always believe the scientists but hey, ho – let’s see if I can help break down this complex class a bit (bearing in mind I don’t have much of a grasp on it myself!)

BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO HYMENOPTERA

Hymenopterans are divided into two main groups, the sub-orders Symphyta (sawflies and wood-wasps) and Apocrita (everything else) the main physical difference being, sawflies have an abdomen fused to the thorax and the others all have some sort of ‘wasp waist’ which is in fact highly modified abdominal segments. Apocrita is then further broken down into Parasitica in which the majority use their ovipositor to lay eggs into a host and Aculeata where, generally, the ovipositor has been modified into a stinger of some sort. Obviously this relates to females only and males of the same species can often look quite different (this is known as sexual dimorphism) – just another joy to add to the mix!

SYMPHYTA (Sawflies and wood-wasps)

Sawflies are so named because their ovipositors are serrated to enable them to saw down into plant material where they then lay their eggs. All sawflies, except the family Cephidae, have a pair of cenchri behind the scutellum that hold the wings in place when the insect is at rest. This is absent from all Apocrita. Unfortunately this is of limited help as, unless they’re flying, their wings are generally folded over the body and you can’t see this detail. Sawflies also have a notch-like division in the first abdominal segment but same problem applies! They come in all shapes, sizes and colours and some of the wood-wasps have a prominent ovipositor. As mentioned above, the main thing to look for is the lack of any ‘waist’.

APOCRITA (Aculeata and Parasitica)

BEES (Apidae):

Social bumblebees and Cuckoo bumblebees

Most people will be familiar with bumblebees, those large, hairy buzzing things that hang around flowers all day. With a little care they can be identified by the pattern of coloured bands on the thorax and abdomen combined with the general shape of the face and length of the tongue. There are three casts – queens, workers and males which are often similar but can be different according to the species. Cuckoo bees, as their name suggests, take over bumblebee nests by kicking out the original queen and so tend to look generally similar to their hosts. The way to tell the difference is in the hind tibia – in female bumblebees it’s shiny, flat and wide with longish hairs on the edges and with cuckoos it’s dull, rounded, narrow and covered in fine hairs. Some cuckoo bumblebees also tend to have noticeably darkened wings.

Honey bees

Honey bees

Fortunately there’s only one species of honey bee in the uk, Apis mellifera, and it’s usually the female worker you see out and about. The males, or drones, are confined to the hive until mating time when they fly high up to find virgin queens and so are rarely seen. It’s worth noting that there are several sub-species of Apis mellifera – The ‘Dark’ or ‘European’ honey bee, the ‘Italian’ honey bee and the ‘Grey’ honey bee to name a few – and interbreeding between them is not uncommon, so there is some colour variation to contend with. The main thing to look for is the noticeably long costal cell in the forewing. Also there are several solitary bees that look similar, so if in doubt double-check!

Solitary bees

Separating the various solitary bees can be a challenge. They come in a range of sizes and colours and although some are obviously bee-like others can be confused with honey bees, bumblebees or wasps if you’re not careful. Also, they are often grouped according to the length and shape of the tongue, which is not very helpful if all you have is a photo, and females and males can also be quite different. While many solitary bees are catholic in their choice of food plant others only feed from a small range of flowers and some only one plant in particular, which can help with identification. Most solitary bees are pollen-gathering and carry their haul on their hind legs or in the case of many members of the Megachilidae family, on pollen brushes under the abdomen but there are also a few cuckoo species. The number of sub-marginal wing cells is often a helpful pointer in determining the family.

WASPS

Social wasps (Vespidae)

Social wasps (Vespidae)

Social wasps are those annoying (to some) yellow-jackets that are attracted to your beer/juice/jam sandwiches in the summer. There are several species and they can be told apart by their faces, specifically by markings (or lack of) on the clypus and by the malar space (the space between the bottom of the eyes and the top of the jaw). The abdominal patterns can also be used but can be variable. The largest social wasp – the Hornet – can be identified by its size and red thorax. Male antennae are longer than the females and the boys are generally seen on flowers in late summer. Wings are held either side of the body at rest.

Potter and Mason wasps (Eumenidae)

These are solitary wasps but closely related to social wasps and as a result are nearly all black and yellow, holding their wings either side of the body at rest. The pronotum reaches back to the tegulae and there is a single spur on the mid tibia. The absence of any markings on the mesothorax helps distinguish them from social wasps who generally have two or four yellow spots.

Digger wasps (Sphecidae)

As suggested by the name, most dig a burrow and load it with prey for their grubs to devour. They are generally slender wasps, many having a broad head and the females often have spiky combs on their forelegs to help with the digging. Their pronotum only forms a small collar which helps separate them from other solitary wasps. Some species have noticeably long, thin, almost thread-like ‘waists’ but there are a few that superficially resemble social wasps. Some are all black but generally they’re black and yellow or black and red and hold their wings over the abdomen at rest.

Spider-hunting wasps (Pompilidae)

Superficially like Digger wasps these little devils use spiders as their prey of choice. As a consequence the females often have long legs, especially the hind femur, equipped with evil-looking spurs. The males are often smaller than the females as all they need to do is mate. They generally have longer antennae than Digger wasps although the general colouring can be similar. Nearly all species have three sub-marginal cells and their pronotum also reaches the tegulae. Like Diggers they hold their wings over the abdomen at rest.

Ruby-tailed wasps (Chrysididae)

AKA Jewel-wasps these are brightly coloured (red/blue/green), metallic looking insects that lay their eggs in a host nest, usually that of a solitary bee or wasp. They tend to have flat or slightly concave undersides and when seen from above appear to have three largish abdominal segments. Some look like they have a stinger but it is in fact an ovipositor.

Ichneumons (Ichneumonidae)

Looking a bit like the Digger and Spider-hunting wasps already mentioned, Ichneumons are a huge family that varies from the tiny to reasonably big and are notoriously difficult to identify. They tend to be slender insects with long antennae and some posses intimidatingly long ovipositors. The front edges of the wings are quite thick as the costa and sub-costa sit right next to each other and they also have an obvious pterostigma.

Velvet ants (Mutillidae)

Despite the name these insects are actually wasps but the females are wingless. There are only two UK species (Mutilla europraea and Smicrosmyrme rufipes) both of which have a brick red thorax and black abdomen with palish yellow markings.

Gall wasps (Cynipidae)

Gall wasps are tiny little things that have fat looking abdomens and sparse, distinctive wing venation. They lay their eggs into plant tissue (often oak trees) causing the host to form swellings or growths known as galls. Galls come in many shapes and sizes from the classic ‘oak apple’ to things that look like a wooly pom-pom to little flattish discs called spangle galls. Association with the host plant is often the best way to identify these little blighters.

ANTS (Formicidae)

There are about sixty species of ant in the UK although only a few are widespread. They are classed as hymenopteran insects because the breeding queens and males have wings with hamuli, although most of the time it’s the wingless workers that we see. Apart from colour (black, red or yellow) ants are usually told apart by their waist (aka pedicel or petiole) which can have one or two sections. Those of the sub-family Myrmicinae have two segments whereas the other sub-families (Formicinae, Dolichoderinae and Ponerinae) have one. Where you find ants is often a good clue to their species.

Recent Comments